Each idea has to be linked to the next idea. Each line of dialogue has to follow from the previous and into the next smoothly. Each scene should connect to the next.

There can't be gaps, where the audience wonders "how did we get from here to there?"

The outline should have the basic structure. It should link each scene.

The detailed continuity should be up to the person doing the storyboard.

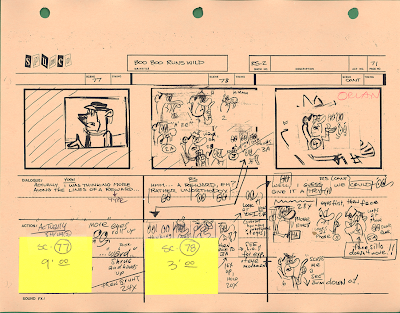

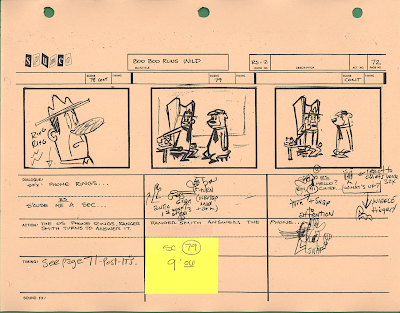

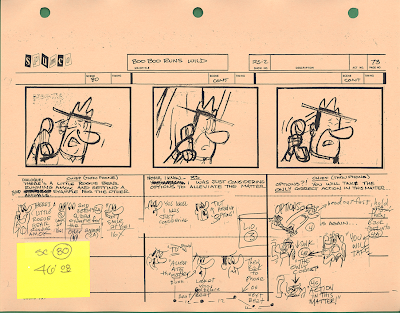

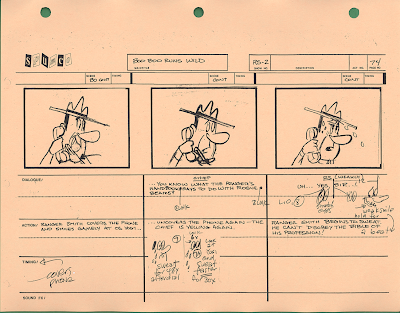

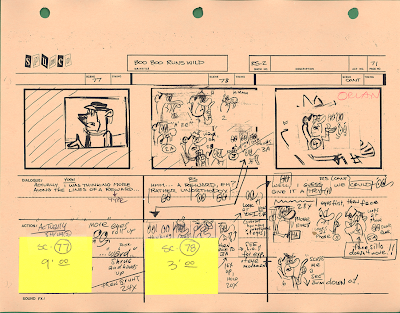

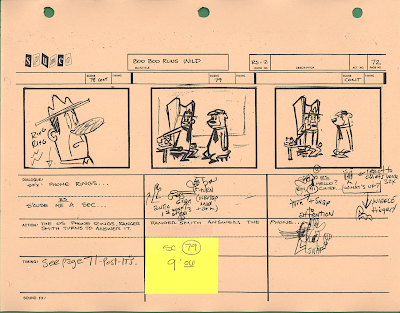

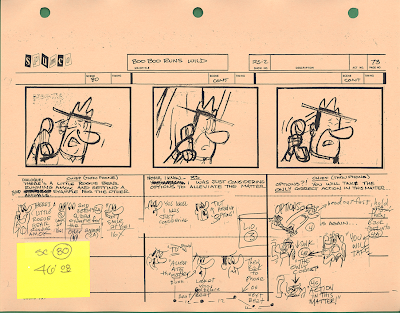

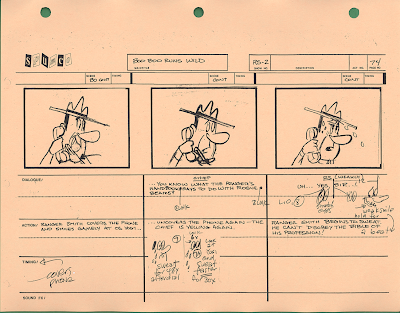

This storyboard was done by Vincent Waller. Those little sketches were done by me, either in the layout poses first and then doodled onto the board to time from, or I doodled them first and then addedd them in the layouts. I don't remember...

This storyboard was done by Vincent Waller. Those little sketches were done by me, either in the layout poses first and then doodled onto the board to time from, or I doodled them first and then addedd them in the layouts. I don't remember...

Either way, pose artists animators, directors and assitant animators each fill in more continuity.

Either way, pose artists animators, directors and assitant animators each fill in more continuity.

The storyboard artist/writer links the dialogue, the action and the acting. Between each major expression, there are smaller expressions that connect them.

The outline is where you contruct your story. The storyboard is where you write it and connect the dots.

There can't be gaps, where the audience wonders "how did we get from here to there?"

The outline should have the basic structure. It should link each scene.

The detailed continuity should be up to the person doing the storyboard.

This storyboard was done by Vincent Waller. Those little sketches were done by me, either in the layout poses first and then doodled onto the board to time from, or I doodled them first and then addedd them in the layouts. I don't remember...

This storyboard was done by Vincent Waller. Those little sketches were done by me, either in the layout poses first and then doodled onto the board to time from, or I doodled them first and then addedd them in the layouts. I don't remember... Either way, pose artists animators, directors and assitant animators each fill in more continuity.

Either way, pose artists animators, directors and assitant animators each fill in more continuity.

The storyboard artist/writer links the dialogue, the action and the acting. Between each major expression, there are smaller expressions that connect them.

The outline is where you contruct your story. The storyboard is where you write it and connect the dots.

Understand Personality

This is not essential, because many cartoons are not about personality. Tex Avery never used layered characters in his MGM cartoons, but still made some of the best cartoons in history.

Disney's characters are one-dimensional (if they are lucky!) but that didn't stop him from being pretty successful.

But you should know enough to not have your characters all of a sudden do or say something that is totally out of character-unless the story supplies a believable reason for it.

Your characters' actions and their dialogue should come out of their character.

Ren doesn't do things the way Stimpy does. Bugs talks and acts different than Elmer, etc.

I had a really good board artist doing a scene for "In The Army". Ren and Stimpy were doing KP duty, peeling potatoes, and in the board Stimpy was cross with Ren. He was chewing out Ren for getting them in trouble with the sergeant over and over again. It was beautiufully drawn, but out of character, so I asked the artist to rework the scenes so that Ren is the mean one and Stimpy thinks that KP duty is a reward. Stimpy almost always thinks that Ren's mischief is a good thing. You have to push him pretty far to upset him.

Needing to understand character seems obvious, but I have yet to meet another cartoon writer who can keep their characters consistently in character. I usually have to do that part myself, but I could sure use some help if someone exists out there! There are a lot of great and funny artists, but less that can create inspired characters and certainly none of the writers can. That's the whole history of the business. Warner Bros. seems to have been the big exception.

Character Treatment

I actually frown on writing up character treatments- a description of your characters' personality traits.

They (TV execs) make you do that when you start a project or pitch one. They make you write a "story bible" and as part of it you have to describe who your characters are and worse, what their catch phrases are.

The bad thing about this is that if you force yourself to try to figure out everything there is to know about your characters before you start making your cartoons, you end up restricting yourself to what you thought you knew about them early on. The execs make you stick to it and your characters are forever limited to being cardboard cutouts.

What you find from actually making cartoons is that you think of many more and better ideas along the way and your characters evolve as they find themselves in new adventures.

Ren and Stimpy, George Liquor, The Ripping Friends and old cartoons all evolved along the way. They would maintain some of their core traits, but they would get more shaded as more stories got produced.

Catch Phrases

If catch phrases happened, they happened by accident. They weren't "created" upfront, like they are now. How many times did you cringe as a kid when you heard "Welcome to the 90s!" or such other writer creations? (Hey share some of the most obnoxious catch phrases from your childhood cartoons here in the comments!)

When I had Ren say "You bloated sac of protoplasm!" and similar things, people would yell them at me at appearances. I would see them on t shirts. People make me say "No sir, I don't like it" all the time. None of the lines in R and S were ever meant to be catch phrases, but they would just catch on, and Nickelodeon would lean on me to use them again. I resisted as much as possible, figuring that funny dialogue in the next cartoons would also catch on naturally.

Characters should issue from your loins

If you are truly a good character creator, you understand your characters from inside. You feel what's right for them, but you allow them to breathe and grow naturally as you make cartoons. They aren't a list of arbitrary traits and catch phrases. They exist and you are just relating their adventures to the audience.

Many of the artists who work with me add shadings-although if they add something that I feel doesn't fit, I suggest something else. Voice actors would also bring new shadings to the characters when we rehearsed the stories, and their inflections would give me ideas for new stories and new ways to develop the characters' traits further.

If you watch the Ren and Stimpy shows, you can see the characters evolve not only in design, but in their personalities too. I would purposely write whole stories just exploring their personality traits-like Stimpy's Invention or Ren Seeks Help.

OK, enough crap...to get to the point, I did write up a character treatment for Ren and Stimpy-not for myself, but for the Nickelodeon executives and for the artists and story crew on the show. Here it is, if you are interested.

I have one for the George Liquor characters too if you ever want me to post it. Let me know.

I have one for the George Liquor characters too if you ever want me to post it. Let me know.

They (TV execs) make you do that when you start a project or pitch one. They make you write a "story bible" and as part of it you have to describe who your characters are and worse, what their catch phrases are.

The bad thing about this is that if you force yourself to try to figure out everything there is to know about your characters before you start making your cartoons, you end up restricting yourself to what you thought you knew about them early on. The execs make you stick to it and your characters are forever limited to being cardboard cutouts.

What you find from actually making cartoons is that you think of many more and better ideas along the way and your characters evolve as they find themselves in new adventures.

Ren and Stimpy, George Liquor, The Ripping Friends and old cartoons all evolved along the way. They would maintain some of their core traits, but they would get more shaded as more stories got produced.

Catch Phrases

If catch phrases happened, they happened by accident. They weren't "created" upfront, like they are now. How many times did you cringe as a kid when you heard "Welcome to the 90s!" or such other writer creations? (Hey share some of the most obnoxious catch phrases from your childhood cartoons here in the comments!)

When I had Ren say "You bloated sac of protoplasm!" and similar things, people would yell them at me at appearances. I would see them on t shirts. People make me say "No sir, I don't like it" all the time. None of the lines in R and S were ever meant to be catch phrases, but they would just catch on, and Nickelodeon would lean on me to use them again. I resisted as much as possible, figuring that funny dialogue in the next cartoons would also catch on naturally.

Characters should issue from your loins

If you are truly a good character creator, you understand your characters from inside. You feel what's right for them, but you allow them to breathe and grow naturally as you make cartoons. They aren't a list of arbitrary traits and catch phrases. They exist and you are just relating their adventures to the audience.

Many of the artists who work with me add shadings-although if they add something that I feel doesn't fit, I suggest something else. Voice actors would also bring new shadings to the characters when we rehearsed the stories, and their inflections would give me ideas for new stories and new ways to develop the characters' traits further.

If you watch the Ren and Stimpy shows, you can see the characters evolve not only in design, but in their personalities too. I would purposely write whole stories just exploring their personality traits-like Stimpy's Invention or Ren Seeks Help.

OK, enough crap...to get to the point, I did write up a character treatment for Ren and Stimpy-not for myself, but for the Nickelodeon executives and for the artists and story crew on the show. Here it is, if you are interested.

I have one for the George Liquor characters too if you ever want me to post it. Let me know.

I have one for the George Liquor characters too if you ever want me to post it. Let me know.