Learn Fundamentals

There is a reason for learning all these basic drawing tools I've been talking about. Once you understand your basic tools, you'll want to do something with them.

By themselves they have no meaning unless you apply them to some purpose.

If you just fill up sketchbooks with floating characters that look neat, that's not really functional. That's good for showing your friends, and it's good if you are studying how certain things look, but it won't help you do an actual job.

That's the next step- using your skills to perform a function.

Applying fundamentals to a purpose- functional art

I have learned (and I learned this slowly) from experience that talent and skill is not enough to be able to do a job.

I have hired many young artists just on the basis of some sketches in their portfolios that indicated to me that they had talent.

Sometimes it paid off fast. A small % of them learned quickly and then after a couple months started doing work that was usable.

Most didn't. Talent and even basic skills isn't enough. I used to assume if you had talent, you could just sit down and bang out a scene.

Everyone learns to function at different rates. Some never do.

It's a sad state of the system today that people can't learn the best way to do functional animation drawings.

The best learning system existed in the 1930s, when all the animation was done in the studio in the country, and under the direction of an experienced animation director.

You started as an inbetweener working for an animator and by tracing his drawings and filling in the inbetweens you learned how to animate.

You learned to leave enough space between your characters for when they had to stretch their arms or jump up or walk out of the scene or sit on a chair. This is stuff you can only learn by doing it, and all that is done outside the country now, so really hardly anyone who makes cartoons today really knows how they are made, because they never learned by doing it themselves.

So it's not the fault of the young artists today, but the system makes it almost impossible to do anything truly animated in a creative way because you just can't afford to train people on the budgets that the studios give you. And the most important jobs are done overseas.

That's what this blog is for, to give young cartoonists as much knowledge and common sense tips to help them teach themselves what will give them the the most skills and more skill and knowledge means you have more tools to create from.

Functions in Animation

Animation is a collaborative medium. There are so many creative steps that go into making a cartoon and every one is important.

Here are some rough functions of some departments:

Storyboards:

These are the drawings that write and tell the story.

The function of a storyboard artist is to make the story make sense, be entertaining, have structure and give some indication of the acting and personalities of the characters.

It's not enough to be able to draw funny characters that float in a sketch book.

You have to be able to draw logical steps in continuity.

The characters to be staged in a way that tells each story point the most effectively.

The characters have to make expressions that not only tell the viewer what they are thinking each step of the way, but tell you in a way that only that particular character would do it.

The expressions have to be

1) funny

2) in character

3) in context of the moment of the story

The same goes for the body poses and gestures.

Now these are just a few functions you have to be able to perform to draw a storyboard.

You also have to have good and logical cutting.

You have to understand how animation works so that you don't storyboard something that is impossible to animate.

You can only really know this by having done some animation and having shot some storyboards on film and then seeing the final animation working and having people who you don't know laugh at the final product.

I'll talk about storyboards more in another post.

Here are some rough functions of some departments:

Storyboards:

These are the drawings that write and tell the story.

The function of a storyboard artist is to make the story make sense, be entertaining, have structure and give some indication of the acting and personalities of the characters.

It's not enough to be able to draw funny characters that float in a sketch book.

You have to be able to draw logical steps in continuity.

The characters to be staged in a way that tells each story point the most effectively.

The characters have to make expressions that not only tell the viewer what they are thinking each step of the way, but tell you in a way that only that particular character would do it.

The expressions have to be

1) funny

2) in character

3) in context of the moment of the story

The same goes for the body poses and gestures.

Now these are just a few functions you have to be able to perform to draw a storyboard.

You also have to have good and logical cutting.

You have to understand how animation works so that you don't storyboard something that is impossible to animate.

You can only really know this by having done some animation and having shot some storyboards on film and then seeing the final animation working and having people who you don't know laugh at the final product.

I'll talk about storyboards more in another post.

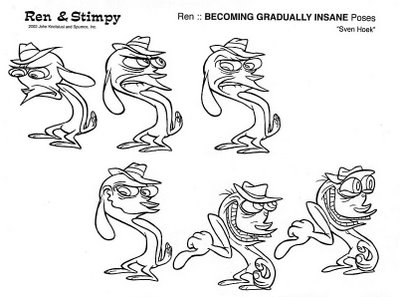

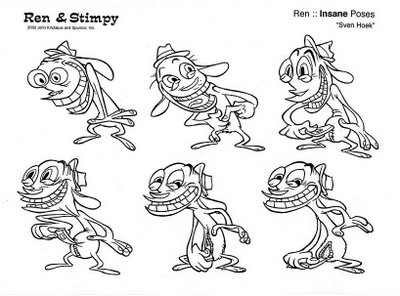

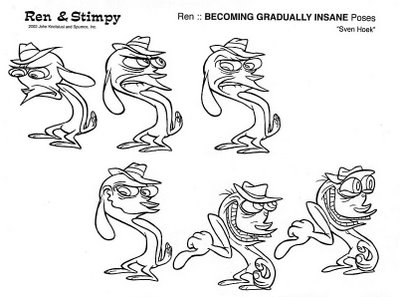

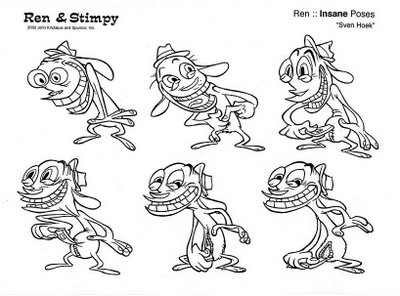

Posing for Animation Layouts

Because animation was done overseas by the time I got into the business, there was no way to control the entertainment though the character drawings in the 1980s, so I came up with a band-aid approach: Doing tons of poses in the layouts.

Doing character layouts is similar to storyboard posing but more detailed and finished.

The functions (besides using all the fundamental drawing tools I've been talking about) are

breaking down the scene into every pose that tells the story and that tells the changes in emotion.

Drawing the characters "on-model". Not on-model in the sense of tracing model sheets like most studios do, but to draw them recognizably as who they are.

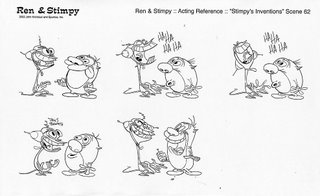

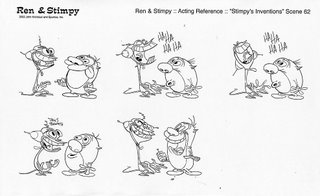

Here's a relatively simple scene below as an example of a functional and creative scene.

Before you draw a scene, you have to analyze the story meaning of the scene and the physical restrictions of the scene. You can't just sit down and be creative and draw in the style of your sketchbook or phone doodles.

Before you draw a scene, you have to analyze the story meaning of the scene and the physical restrictions of the scene. You can't just sit down and be creative and draw in the style of your sketchbook or phone doodles.

You need to analyze...

the Story purpose: In this scene above, you have to tell the audience in a funny way that:

1 The Happy Helmet has just kicked in and Ren is feeling his first moment of pure happiness.

2 Stimpy is an idiot and has no clear expression unless something moves.

3 Ren laughs joyously, innocently, not crazy yet

4 Stimpy sees Ren laugh and has a "pre-reaction" -slight surprise before:

5 Ren stops laughing/moving and Stimpy goes retarded again

6 Ren starts to talk, all happy now

7 Stimpy reacts- he joins in with Ren's new found emotion

Physical requirements:

This means there has to be enough space in the scene for the characters to do all the story things they have to do.

Ren basically moves up and down, so he has to have space above his head to move up.

This sounds simple, but you wouldn't believe how many layout artists (me too) who don't leave enough room for the action to happen in and have to go to the xerox machine to shrink down and reposition everything.

The expressions have to be clear, specific and in context and have to wrap around the construction of the characters.

So... having to balance all the story requirements and physical requirements of the scene drags your brain down and makes it hard to be creative. You have to work out a lot of creative and mechanical problems at the same time.

You might wonder: Where is there room for creativity here if the story is already written?

In the quality and entertainment value and humor of the drawings. In fact, to me this is the most creative and important step in the animation process-drawing the drawings that the people see. These drawings are the entertainment. They are the performers of the show and every other job on a show is subservient to the performance.

It's a lot easier to do a free and creative fun looking drawing in a sketchbook when you don't have anything to think about except how cool the individual floating drawing is, but as soon as you sit down to do functional drawings that have a consecutive order and have to build emotionally and be in the right place, then you find out what drawing really means.

This process of functioning makes you stiff. All of a sudden your drawings are lifeless and boring and awkward. This is natural to most artists and the only cure for it is to keep doing it until you are able to loosen up and function at the same time. This is a very frustrating balance and it breaks a lot of cartoonists. It separates the boys from the men. I've seen people give up just because they hate that stiff period while they are learning something new that they haven't done before. Every real artist goes through this constantly (unless they settle into a comfortable cliched simple style). You have to eat the pain and get used to hating your drawings every time you try to improve yourself. It's natural.

This takes time and practice. Start now! If you want to have cartoons that are filled with funny drawings and acting you better get your fundamental skills down as soon as possible and start doing whole scenes! Once you get confident and loose you will have a lot of fun.

Every expression and pose in here is completely specific to the progression of the story. There are expressions that were created for the scene because no stock expression would do. Of course after the cartoon, you've probably seen some of these expressions again out of context in other cartoons.

Every expression and pose in here is completely specific to the progression of the story. There are expressions that were created for the scene because no stock expression would do. Of course after the cartoon, you've probably seen some of these expressions again out of context in other cartoons.

The drawings look free and crazy and fun, but they are not at all arbitrary. They are suited to the needs of the scene. I wouldn't be able to think of expressions like this arbitrarily if I didn't have a funny story to inspire me. I could think of arbitrary crazy non-functional drawings and I do on my napkins at Lido's, but those drawings are only seen by 2 or 3 people and they sure wouldn't affect the world the way tailored wacky drawings to a story can.

The drawings look free and crazy and fun, but they are not at all arbitrary. They are suited to the needs of the scene. I wouldn't be able to think of expressions like this arbitrarily if I didn't have a funny story to inspire me. I could think of arbitrary crazy non-functional drawings and I do on my napkins at Lido's, but those drawings are only seen by 2 or 3 people and they sure wouldn't affect the world the way tailored wacky drawings to a story can.

Doing character layouts is similar to storyboard posing but more detailed and finished.

The functions (besides using all the fundamental drawing tools I've been talking about) are

breaking down the scene into every pose that tells the story and that tells the changes in emotion.

Drawing the characters "on-model". Not on-model in the sense of tracing model sheets like most studios do, but to draw them recognizably as who they are.

Here's a relatively simple scene below as an example of a functional and creative scene.

Before you draw a scene, you have to analyze the story meaning of the scene and the physical restrictions of the scene. You can't just sit down and be creative and draw in the style of your sketchbook or phone doodles.

Before you draw a scene, you have to analyze the story meaning of the scene and the physical restrictions of the scene. You can't just sit down and be creative and draw in the style of your sketchbook or phone doodles.You need to analyze...

the Story purpose: In this scene above, you have to tell the audience in a funny way that:

1 The Happy Helmet has just kicked in and Ren is feeling his first moment of pure happiness.

2 Stimpy is an idiot and has no clear expression unless something moves.

3 Ren laughs joyously, innocently, not crazy yet

4 Stimpy sees Ren laugh and has a "pre-reaction" -slight surprise before:

5 Ren stops laughing/moving and Stimpy goes retarded again

6 Ren starts to talk, all happy now

7 Stimpy reacts- he joins in with Ren's new found emotion

Physical requirements:

This means there has to be enough space in the scene for the characters to do all the story things they have to do.

Ren basically moves up and down, so he has to have space above his head to move up.

This sounds simple, but you wouldn't believe how many layout artists (me too) who don't leave enough room for the action to happen in and have to go to the xerox machine to shrink down and reposition everything.

The expressions have to be clear, specific and in context and have to wrap around the construction of the characters.

So... having to balance all the story requirements and physical requirements of the scene drags your brain down and makes it hard to be creative. You have to work out a lot of creative and mechanical problems at the same time.

You might wonder: Where is there room for creativity here if the story is already written?

In the quality and entertainment value and humor of the drawings. In fact, to me this is the most creative and important step in the animation process-drawing the drawings that the people see. These drawings are the entertainment. They are the performers of the show and every other job on a show is subservient to the performance.

It's a lot easier to do a free and creative fun looking drawing in a sketchbook when you don't have anything to think about except how cool the individual floating drawing is, but as soon as you sit down to do functional drawings that have a consecutive order and have to build emotionally and be in the right place, then you find out what drawing really means.

This process of functioning makes you stiff. All of a sudden your drawings are lifeless and boring and awkward. This is natural to most artists and the only cure for it is to keep doing it until you are able to loosen up and function at the same time. This is a very frustrating balance and it breaks a lot of cartoonists. It separates the boys from the men. I've seen people give up just because they hate that stiff period while they are learning something new that they haven't done before. Every real artist goes through this constantly (unless they settle into a comfortable cliched simple style). You have to eat the pain and get used to hating your drawings every time you try to improve yourself. It's natural.

This takes time and practice. Start now! If you want to have cartoons that are filled with funny drawings and acting you better get your fundamental skills down as soon as possible and start doing whole scenes! Once you get confident and loose you will have a lot of fun.

Every expression and pose in here is completely specific to the progression of the story. There are expressions that were created for the scene because no stock expression would do. Of course after the cartoon, you've probably seen some of these expressions again out of context in other cartoons.

Every expression and pose in here is completely specific to the progression of the story. There are expressions that were created for the scene because no stock expression would do. Of course after the cartoon, you've probably seen some of these expressions again out of context in other cartoons. The drawings look free and crazy and fun, but they are not at all arbitrary. They are suited to the needs of the scene. I wouldn't be able to think of expressions like this arbitrarily if I didn't have a funny story to inspire me. I could think of arbitrary crazy non-functional drawings and I do on my napkins at Lido's, but those drawings are only seen by 2 or 3 people and they sure wouldn't affect the world the way tailored wacky drawings to a story can.

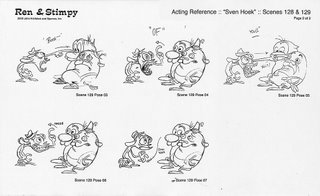

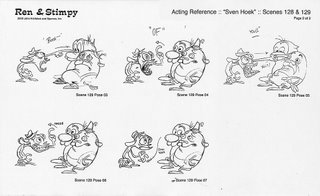

The drawings look free and crazy and fun, but they are not at all arbitrary. They are suited to the needs of the scene. I wouldn't be able to think of expressions like this arbitrarily if I didn't have a funny story to inspire me. I could think of arbitrary crazy non-functional drawings and I do on my napkins at Lido's, but those drawings are only seen by 2 or 3 people and they sure wouldn't affect the world the way tailored wacky drawings to a story can.Here's a scene that a talented Spumco cartoonist was struggling with. The more things that happen in a scene, the harder it is to coordinate them together. The scene becomes way harder to plan. There were a ton of complex problems to work out in this scene.

There are a lot of long long scenes in Spumco cartoons. A general theory I have heard at the Saturday morning (and prime time) studios is that you should keep your scenes short, keep cutting at random from a long shot to a close up to a medium shot etc. Why? "To keep the film interesting". That's because nothing interesting happens in many modern cartoons, so you have to have quick cuts to fool the audience into thinking the film is moving along.

I've had scenes without a cut that lasted more than a minute and people laughing all through them. That's because I make sure there is always something happening, not just flapping lips.

Like this one.

This scene was extremely hard to work out functionally and it took 3 of us: Mike F., Bob Camp and me all helping each other.

This scene was extremely hard to work out functionally and it took 3 of us: Mike F., Bob Camp and me all helping each other.

Stimpy is cute, stupid and sincere and has to press a button with clear silhouettes.

Learn your fundamentals and then start to function!